A very brief overview on distributing wealth fairly

There are lots of things society might want to distribute equally, but wealth probably isn’t one of them. In this post we go over alternative ways to allocate money amongst a population.

This is a follow-up to the post What makes a fair and equal society?, where we define a fair society as a state or nation whose population have agreed in advance how assets (such as wealth, freedom, voting rights, etc.) should be distributed, and thereafter enforce this distribution. But although people may agree to distribute some of these assets equally to all individuals — for example legal rights, voting rights and opportunity — it’s not clear that they would feel the same way about material assets such as money and property. There are many differing opinions about how one might distribute this sort of asset (termed ‘material wealth’, sometimes shortened simply to ‘wealth’) if not evenly, and this post will give a brief overview of the different alternatives (the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy’s entry on distributive justice, found in the references, goes into all of them in more detail) together with a short discussion of the problem of choosing between them. It concludes with the current standpoint of this site, which we will expand on in future posts.

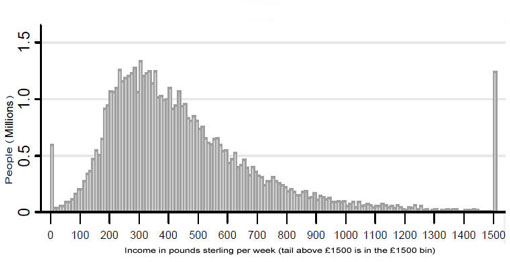

If we are going to talk about how to distribute wealth, we need to familiarise ourselves with the technical aspects of a society’s wealth distribution. A wealth distribution graph shows the spread of individual wealth across the population. In the following example, the measure of wealth will be income. Below is the UK one from 2007-8. The shape changes every year depending on what each member of the population earns.

[Brewer et al, 2009]

You may have come across this graph in a different form. The Gini coefficient is a number which condenses the profile of the distribution to a single figure (with 1 meaning that everyone is earning the same amount and 0 implying that one person earns all the wealth) and is a popular (if simplistic) way of summarising this distribution.

What should the wealth distribution look like in an ideal society? Some politicians and political commentators claim that incomes should be broadly equal, arguing for instance that “it is important that [the pursuit of more income equality] is an explicit goal [of government]” (Miliband, 2010). But is inequality of income or wealth (or inequality of outcome in general) necessarily a bad thing? It all depends on what principle of distributive justice you adhere to — if everyone were to agree that the correct way to allocate wealth is to give all individuals exactly the same amount, then people earning different incomes would indeed be a bad thing. This stance of enforcing equal wealth is known as strict egalitarianism and because it entails everyone earning equal incomes it compels a nation to aspire to the distribution on the left:

Some followers of socialism take this view; that in a fair society we should all earn the same income regardless of our personal circumstances. Others argue that what is important is that, as a generation, we should start off with equal incomes, but our individual income should be allowed to grow or shrink depending on how hard we choose to work, or how we invest our money. This second view is known as the starting-gate principle of distributive justice, and one possible way incomes might eventually fan out is shown above on the right. Crucially, of these two cases, only strict egalitarianism states exactly what the wealth distribution must look like. In the case of the starting-gate principle of distributive justice, it’s impossible to measure whether the principle is being achieved from the shape of the distribution: while you can tell if people start off with the same amount of money, after this initial period the principle cannot predict the eventual distribution shape. Similarly, because measures like the Gini coefficient are estimates of income only (not hard work or other choices), they are only useful for strict egalitarians.

Other theories of distributive justice can, under certain conditions, be checked by the shape of the distribution: one such theory is the Difference Principle, which states that wealth should only be distributed in ways that increase the wealth of the poorest. Under this principle, the wealth distribution is allowed to fan out, but only if it fans upwards in such a way that the poorest are better off than if no redistribution had happened (Rawls, 1971, 1993). Unfortunately, it’s a bit difficult to know which policies would best comply with the Difference Principle. Imagine a government which taxes its population, and gives the resulting cash to the poor. This probably corresponds to the difference principle better than not doing any redistribution at all. But an economist might suggest that giving money to rich bankers is better; bankers may invest it more wisely, raising the nation’s living standards to the point where the poor end up with more wealth than if you had given them money directly. Because the Difference Principle says to give wealth to whomever makes the poor better off, the government, not knowing in advance which tactic would actually raise the standards of the poor, would have to try both approaches before coming to a decision.

Another possible principle that can be theoretically checked by the shape of the graph is utilitarianism. This principle states that the graph shape is correct if and only if it maximises the total sum of happiness in the population (Mill, 1863). But the correct shape for this principle is (as with the starting-gate principal) difficult to determine — this time because no-one knows what shape the graph would have to be for this maximisation to happen, short of continually giving people different amounts of money and then asking them how happy they are.

Perhaps you prefer the idea of people only getting money if they deserve it. Some philosophers have expanded the starting-gate principle by using more complex criteria to decide when individuals have justly earned wealth. These desert-based principles (not referring to sandy deserts, despite the spelling) argue that you should only lose or gain assets if you deserve to (under different interpretations of ‘deserve’; for instance those of Sadurski 1985, Milne 1986, Lamont 1997 and many others). Desert-based principles are intuitively popular, but fairly difficult to define in a way that everyone can agree on. And like the starting-gate principle, even if we could agree on a definition of ‘deserve’, we couldn’t tell just by looking at the distribution graph if it was being upheld.

Inevitably, this post simplifies a number of issues in order to make the discussion more straightforward. Most distributive justice principles do not limit themselves to wealth, but also consider other factors such as wellbeing and health. Moreover, working out how to choose between principles is easier said than done. Almost all principles rest on complex assumptions which are tricky to verify, making comparison difficult. Yet we can afford to feel optimistic for a number of reasons. First, consensus is growing that individuals’ earnings should be allowed to fluctuate during their lifetimes (few modern thinkers advocate strict egalitarianism1). Second, it is now generally accepted that the choices each of us make should play a part in these fluctuations. These two assertions, general as they may seem, allow us to narrow our search to only those principles that abide by them.

The remaining candidate principles hint at a further promising corollary. As Lamont & Favor (2007) note, authors of principles that adhere to the above two assertions tend to utilize the currency-based free market economy2 to direct and guide wealth distribution shape. While the free market is not itself a formal principle3, as a technique for distribution it has a number of attractions: the versatility of money as a proxy for material goods allows for easy comparisons of value; private enterprise broadly rewards hard work with comparative amount of wealth; some of aspects of the market system (like competition) have the useful side-effect of raising efficiency; whilst the addition of creative taxes offer ways to redistribute assets where the markets can’t. These features make the free market economy at least partially consistent with a number of the distributive justice principles mentioned above: the Difference Principle (because rises in efficiency often cause material goods to become cheaper, thus increasing the material assets of the poor); many desert-based principles (because individuals get to earn money based on how hard they work); and utilitarianism (because individuals are free to spend money on what they think will make them the most happy). Perhaps then, if there is a pre-eminently rational way to distribute wealth, it’s not so very different from the one we currently practice.

The question is: how different? And if we are so close, why have we yet to construct a principle of distributive justice that everyone can agree on? These are questions we will be expanding on in posts to come.

1 Although some argue that a high Gini coefficient is empirically shown to statistically reduce health-related and social problems in a society (Wilkinson and Pickett, 2009). Like all good science though, these results are disputed (Saunders, 2010; Snowdon, 2010; Cornia and Court, 2001).

2 A market economy is a society with a framework that allows citizens to exchange property and services at will. Usually this is done through the medium of currency, and usually the framework is legally enforced. The term free market economy is used to stipulate that citizens have the right to choose what price they sell/pay for another’s property with little (if any) government participation. There are other variations: a laissez-faire market economy is an economy where the government are not allowed to intervene in this transaction at all.

3 Although a principle of distributive justice called Entitlement Theory (Nozick, 1974) is one attempt to formalise a variant of the free market economy as a principle.

Sources

- “it is important that [the pursuit of less income inequality] is an explicit goal [of govenment”Ed Miliband interview with left foot forward blog http://www.leftfootforward.org/2010/07/ed-miliband-income-equality-explicit-goal/ [2010]

- UK income distribution graph: Mike Brewer, Alastair Muriel, Divid Phillips, Luke Sibieta, Poverty and inequality in the UK 2009, IFS Commentary C109, The Institute for Fiscal Studies [2006]

- Lamont J and Favor C “Distributive Justice”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy(Winter 2007 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), covers all of these views in more detail http://www.seop.leeds.ac.uk/entries/justice-distributive/

- Weale, A ‘Equality’ The Shorter Routledge Encyclopaedia of Philosophy, Routlegde [2005]

- Richard Wilkinson, Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better, Allen Lane, [2009]

- Peter Saunders, Beware False Prophets, Policy Exchange [2010]

- Christopher John Snowdon The Spirit Level Delusion: Fact-checking the Left’s New Theory of Everything, Democracy Institute/Little Dice [2010]

- Giovanni Andrea Cornia and Julius Court, Inequality, Growth and Poverty in the Era of Liberalization and Globalization, UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU/WIDER) [2001]

- Abigail Davis, Donald Hirsch and Noel Smith. A Minimum Income Standard for Britain in 2010. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [2010] http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/MIS-2010-report_0.pdf

- Nozick, Robert, Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Basic Books [1974]